Seven years ago, Putney residents simply wanted a better high street. Cleaner air, safer crossings, a place where people might actually want to linger. What they got instead was an £835,000 junction redesign that has created gridlock, required an emergency £169,000 fix, and will be examined by councillors this Thursday amid mounting public anger.

Documents obtained and gathered by Putney.news reveal a pattern of compromises, rejected safety designs, and warnings ignored. This is the story of how a local improvement project became a cautionary tale about transport governance in London.

The Optimistic Beginning (2017-2019)

It started with hope. In February 2017, local councillors requested improvements to Putney High Street. The vision was ambitious but achievable: better air quality, enhanced public realm, safer streets for pedestrians and cyclists, and a thriving town centre that could compete with other London high streets.

Putney had a problem everyone could see. Air pollution levels were among the worst in London. The high street recorded the first nitrogen dioxide limit breaches in the capital in 2016. Over 100 buses per hour squeezed through the narrow street at peak times, accounting for 68% of nitrogen oxide emissions.

But there was also optimism. The council appointed consultants AECOM to develop solutions. By February 2018, they had approved a comprehensive deliverables plan costing £640,000 for the first phase. The plan included Copenhagen crossings, improved cycle parking, tree planting, and upgrades to key junctions including the critical intersection at Putney Bridge.

Local stakeholders were supportive. The newly formed Positively Putney Business Improvement District pledged funding. Wandsworth Living Streets and the Putney Society joined a stakeholder group to help shape the vision. Everyone wanted Putney to be better.

The promise was clear: better air, safer streets, thriving shops.

The COVID complication (2019-2021)

Then came the twin disasters that would shape everything that followed.

In April 2019, Hammersmith Bridge closed to motorised traffic following the discovery of critical structural faults. Traffic that had crossed there now had to use alternative routes, including Putney Bridge. The displacement was immediate and severe.

Initial traffic surveys were conducted in October 2019, six months after Hammersmith Bridge closed. This data was used for the first round of modelling. But as the design process dragged on, something far more disruptive arrived.

In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic brought London to a standstill. Work on Putney High Street stopped for two months. Traffic patterns became completely abnormal as lockdowns emptied the streets and the government ordered people to work from home.

By 2021, with the modelling process still incomplete, TfL asked for revalidation of the traffic data to ensure it remained relevant. The council conducted new surveys on 15 and 18 July 2021 – a moment that would prove to be the worst possible time to measure “normal” traffic.

The measurements were taken just days before “Freedom Day” – July 19 – when England lifted most COVID restrictions. The work-from-home guidance ended that day, but the government explicitly told employers to ensure a “gradual return to the workplace over the summer.” London was in massive transition. Some workers were still at home, others were beginning to return, but working patterns were far from normal. The Delta variant was surging, with government advisers predicting up to 200 deaths per day.

Yet this snapshot – collected just after the Hammersmith Bridge closure, and again in the midst of the largest shift in working patterns in modern history – became the baseline for the entire junction redesign.

TfL insisted on using the July 2021 data. The standard London-wide modelling assumption at the time was that Hammersmith Bridge would reopen in 2026. The junction was being designed not for the traffic conditions that would actually exist in 2024, but for a moment frozen in pandemic transition.

The rejection period (2021-2022)

By summer 2021, AECOM had developed several options for the junction redesign. What happened next reveals the power dynamics that govern London’s streets.

November 2021: The Cyclops option

Cyclists and safety advocates had reason to hope. AECOM proposed a “Cyclops” junction, the gold standard for cyclist safety. The design would completely separate cyclists from motor traffic using protective islands and dedicated signal phases. Pedestrians would get shorter crossing times. It was optimal for vulnerable road users.

Documents show the proposal went to TfL’s Road Space Performance Group. The verdict was swift and final: unacceptable impact on traffic capacity. The Cyclops design would cause “gridlock in Putney,” according to stakeholder meeting minutes, and “would never be accepted by TfL.”

December 2021 to April 2022: Compromise after compromise

The council tried to salvage something. They proposed “cycle gates” with staggered crossings. Still rejected. They proposed cycle gates with straight-through crossings, which would eliminate the “all red” phase that stopped all vehicles. In April 2022, TfL turned this down too due to “unacceptable capacity and journey time implications.”

Each rejection pushed the design further away from safety and closer to traffic flow. And hanging over everything was a deadline that concentrated minds: the Future High Streets Fund required completion by March 2024. The council had £344,732 at risk. Accept TfL’s demands or lose the money.

As one July 2022 stakeholder meeting document put it: “To revisit proposals at concept stage without technical expertise of traffic modelling would not be productive at this stage requiring further expense on abortive traffic modelling work and lead to loss of Future High Street Funding.”

The council was trapped between TfL’s veto and the funding cliff edge.

The forced compromise (2022-2023)

By summer 2022, the council capitulated. They accepted a design that pleased almost nobody.

The design nobody wanted

Cyclists got cycle gates with staggered crossings, but nothing like the Cyclops protection they’d hoped for. Pedestrians got complex multi-stage crossings that prioritised keeping traffic moving. Drivers got a junction that was still congested but now with different signal phases. The council knew it was inadequate but felt it was the best they could achieve given TfL’s constraints.

At the November 2022 stakeholder meeting, members were told the decision was final. This was “the best that can be achieved given the clear balances and constraints.” The target implementation date was set for summer 2023.

Documents from this period reveal a design process driven not by what was safest or best, but by what TfL would approve and what the funding deadline would allow. Traffic capacity trumped all other considerations.

The delayed delivery (2023-2024)

Summer 2023 came and went with no junction changes. The promised implementation didn’t happen. The official reason: “TfL signal contractor availability.” The closure of Wandsworth Bridge for urgent repairs added further complications.

Finally, in September 2023, the Transport Overview and Scrutiny Committee approved the design unanimously. No dissent was recorded in the minutes. The opposition didn’t challenge it. Perhaps everyone was simply exhausted by the years of wrangling, or perhaps they trusted that the extensive modelling had produced a workable solution.

In December 2024, 18 months late and costing £835,000, the new junction was finally implemented. Within days, residents were describing “chaos.” Traffic backing up far beyond anything predicted. Buses stuck in gridlock. Parents unable to get children to school on time. Elderly residents in tears at public meetings.

Something had gone badly wrong.

The unraveling (2025)

January to May: Growing crisis

Through the early months of 2025, the problems intensified. Congestion was worse than before the redesign. Businesses complained about lost customers unable to reach the high street. Residents began organising, demanding answers from the council.

June: The discovery

In June 2025, four months into the crisis, the council discovered a critical error. The signal timings installed at the junction didn’t match the timings AECOM had modelled and TfL had approved.

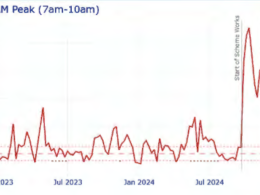

The data was stark. During the morning peak, Lower Richmond Road had lost 10 seconds of green time for the left turn and 4 seconds for the right turn compared to the approved model. Putney Bridge Road had lost 21 seconds. These weren’t minor tweaks, they were substantial differences that fundamentally changed how the junction operated.

The signals had been optimised to prioritise north-south traffic through Putney High Street at the expense of the east-west approaches. Lower Richmond Road and Putney Bridge Road were getting squeezed, creating the backup congestion that residents were experiencing daily.

TfL was informed. The response was slow.

July-August: Public anger peaks

In July and August, the Putney Action Group conducted a survey. The results were damning: 1,373 responses, overwhelmingly critical. The council said it took the feedback “seriously” but still no fixes came.

By now, hundreds of residents were showing up to public meetings, confronting the council leader. One resident reported missing a hospital appointment because “the bus never got through on time.” Another described having to “allow over an hour just to get across Putney Bridge for medical treatment.” Parents said they couldn’t get children to school on time. One woman with a four-year-old daughter told a public meeting: “I cycle less because I now have a daughter. I don’t feel safe on the very congested roads.”

October: Emergency fixes

Four months after discovering the signal timing errors, in October 2025, TfL finally implemented emergency fixes. The changes cost an additional £169,000. Bus Stop P was relocated. Signal timings were tweaked to give Lower Richmond Road an extra 6 seconds in the morning peak and 3 seconds in the evening. Putney Bridge Road got 2 extra seconds.

But the fundamental problems remained. The junction had been designed using abnormal traffic data, optimised for capacity over safety, and implemented with incorrect signal timings. The fixes were patches on a flawed foundation.

November: The reckoning

A comprehensive post-implementation review by AECOM, completed in November 2025, confirmed what residents already knew. The report’s key finding was damning: “The signal timings have not been implemented as modelled by AECOM and approved by TfL.”

When AECOM ran the actual observed signal timings through their model, it replicated the queues and congestion residents were experiencing. The model had been reasonably accurate – it was the implementation that had failed.

The council’s own report to the Transport Committee, scheduled for November 21, admitted to “unexpected congestion.” It was a masterpiece of understatement.

The pattern revealed

This wasn’t just about one junction. The Putney saga reveals systemic failures in how London governs its transport network.

TfL’s unaccountable veto power

Transport for London, an unelected body, has effective veto power over junction designs on London’s Strategic Road Network. Local councils must get TfL approval. When TfL prioritises traffic capacity over cyclist safety, as documents show happened repeatedly in Putney, councils have limited recourse. The Cyclops design was rejected not because it was unsafe or unworkable, but because it didn’t meet TfL’s capacity requirements.

Funding as blackmail

The March 2024 deadline for Future High Streets funding created a gun-to-the-head scenario. Accept TfL’s demanded compromises or lose £344,732. This isn’t collaborative planning; it’s coercion through budget pressure. Councils are forced to choose between imperfect designs and no funding at all.

The wrong data

The junction design was based on two sets of traffic data, both collected under abnormal conditions. The initial October 2019 surveys were conducted six months after Hammersmith Bridge closed, capturing displaced traffic patterns. When TfL demanded revalidation due to the prolonged design process, the July 2021 data was collected at the worst possible moment – just as “Freedom Day” was lifting work-from-home guidance but before any return to normal working patterns.

Yet the council’s own analysis, presented in the November 2025 report, reveals the fundamental problem: traffic volumes on Putney Bridge in 2024 were actually lower than in 2018, before Hammersmith Bridge closed and before COVID. The modelling assumed conditions that no longer existed – or perhaps never would exist again. The junction was designed for a traffic scenario that proved to be a phantom.

No accountability for implementation

Four months passed between discovering the signal timing errors and implementing fixes. Four months of daily gridlock for thousands of residents while bureaucracy ground slowly forward. Nobody was held accountable. Nobody resigned. Nobody even apologised in clear terms.

Monitoring? What monitoring?

The junction was implemented in December 2024. Problems were immediate and obvious. Yet it took until June 2025 for the council to discover that the wrong signal timings had been installed. Where was the monitoring? Where were the post-implementation checks that should have caught this within days?

The human cost

Behind the bureaucratic failures are real people. Elderly residents unable to cross complex junctions safely. Parents driving children to school through gridlock, arriving late. Business owners watching customers give up rather than fight through traffic. Bus passengers enduring longer journey times. Cyclists still feeling vulnerable despite the promised improvements.

This is a million pounds of public money – £835,000 for the junction, £169,000 for emergency fixes – that has made people’s daily lives measurably worse. The air quality improvements that started this whole process seven years ago? Harder to achieve when traffic is gridlocked.

Looking forward

Thursday’s Transport Overview and Scrutiny Committee meeting will examine this mess. Councillors will have the AECOM report, the traffic data, and seven years of documents showing how we got here. The questions they should ask are fundamental:

- Why did TfL reject safer designs in favour of traffic capacity?

- Why was data collected during abnormal conditions used as the baseline?

- How did signal timings get implemented incorrectly, and why did it take four months to discover?

- Who is accountable when junction redesigns fail this badly?

- What changes to the planning and approval process will prevent this happening again?

- What do we do now about Putney Bridge junction?

But the real question is whether the governance system that created this disaster is capable of fixing it. When TfL can veto local designs, when funding deadlines force compromises, when implementation errors go undetected for months, when nobody takes responsibility for failure, can this system produce good outcomes for residents?

Putney has become a case study in what happens when transport governance prioritises traffic flow over people, when bureaucratic processes override local knowledge, when accountability is diffused across organisations until nobody is truly responsible.

Seven years later

In February 2017, councillors asked for a better Putney High Street. Cleaner air. Safer streets. A place where people want to be.

Seven years, £1 million, countless meetings, rejected designs, pandemic disruptions, data collection errors, signal timing mistakes, and emergency fixes later, residents are still waiting.

The junction works for the traffic models. It just doesn’t work for the people who live here.

The Transport Overview and Scrutiny Committee meets Thursday, November 21, 2025, to examine the Putney Bridge junction redesign. Documents, including the full AECOM post-implementation review, are available on the Wandsworth Council website.

DOCUMENT TRAIL

This investigation is based on:

- Traffic data comparisons: 2018, 2021, 2024, and 2025

- Paper 17-81 (Feb 2017): Original Putney High Street improvement request

- Paper 18-65 (Feb 2018): Deliverables plan approved

- Paper 21-032 (Feb 2021): Project update noting COVID delays

- Paper 22-331 (Nov 2022): Junction design approval documenting TfL rejections

- Paper 23-304 (Sept 2023): Final committee approval with funding deadline pressure

- Paper 25-398 (Nov 2025): Admission of implementation failures

- WBCFOI10409: Stakeholder meeting minutes (July 2022, Nov 2022, Feb 2023) detailing rejected Cyclops and cycle gate options

- AECOM Post-Implementation Review (Nov 2025): Technical analysis of signal timing errors

- Appendix 3 (Paper 25-398): Documentation of signal timing discrepancies

An interesting and useful account, but one that misses out on the underlying problem: too many cars!

Seriously, there’s simply too much traffic for a road network that, however it is organised (and yes, it could have been better organised) is not capable of coping with the traffic. And simply providing more road space (how, by bulldozing half of PHS?) won’t work because as been endlessly shown, increasing road space encourages more drivers to use it with the result that you still end up with congestion but more cars = more pollution.

At some point the government must grasp the nettle and introduce measures (variable, dynamic road pricing being the obvious way) to reduce the use of cars to those who must drive, not those who want to. It will be difficult in the face of a hysterical car lobby (“Freedom of the roads!”) and it will take more courage than the current or any prospective government has, but its the only way.