Email committee members a summary of the council report findings and resident survey results to inform Thursday’s meeting.

Our full summary of the council report is available here.

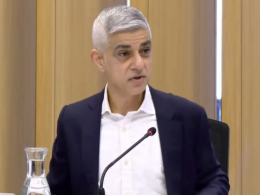

When hundreds of Putney residents confronted Council Leader Simon Hogg at St Margaret’s Church last month, they wanted answers about why the redesigned Putney Bridge junction has created mile-long queues and turned residential streets into rat-runs.

The council’s long-awaited report [pdf] to next Wednesday’s Transport Committee provides some answers but the full picture reveals as much about what the authorities chose to measure as what they found.

The report’s central finding – that traffic signals weren’t implemented as modelled – raises a critical accountability question that the document doesn’t answer: how did this happen?

If Transport for London (TfL) truly implemented different signal timings than those approved, this represents a significant operational failure at London’s traffic authority. But the report provides no explanation of how the discrepancy occurred, who was responsible for catching it, or when it was first discovered.

Putney.news has submitted Freedom of Information requests to both TfL and Wandsworth Council to establish the facts. If the signal timing failure is verified, the junction may indeed be salvageable with the correct settings. If it isn’t, if the approved timings actually were implemented, then the council’s modelling fundamentally failed to predict the outcome, which raises more serious questions about the entire design process.

The report states that when AECOM input the wrong timings into their 2021 model, it “closely replicate[d] the queues observed on site.” This is presented as vindication of the modelling. But it doesn’t answer a more important question: what congestion levels did the approved model predict? Did the council knowingly accept significant queuing on Lower Richmond Road and Putney Bridge Road as an acceptable trade-off for improvements elsewhere?

A junction designed for one outcome

The report’s eight-paragraph section titled “Why not revert to the old layout” makes the council’s priorities unmistakably clear.

The primary justification against reverting is pedestrian island sizes. TfL’s streetscape design guide requires minimum widths of 2.5 metres and 4-metre offsets between staggered crossings. The old layout didn’t meet this standard.

This is a legitimate safety concern. But it’s also the only substantive technical argument in the section. The remainder essentially argues that the benefits to pedestrians and cyclists outweigh the costs to motorists – a policy choice presented as a technical inevitability.

Consider the framing: the report describes the old Lower Richmond Road layout’s two approach lanes as “really equivalent to 1.2 lanes at best” because vehicles had to merge onto Putney Bridge. This is accurate. But having made that point, the report doesn’t grapple with why the new single-lane design, which also feeds into the same single-lane bridge, has created such severe queuing.

The answer appears elsewhere in the report: signals are now “optimised to prioritise movements along the Putney High Street and Putney Bridge corridor, resulting in less green time for Putney Bridge Road and Lower Richmond Road.” This is the fundamental design choice, and it explains why even with 5,000 fewer vehicles crossing the bridge daily than in 2018, those two approaches face unprecedented congestion.

The junction was designed to solve a specific problem, that of poor pedestrian crossings and unprotected cyclists, and it has largely succeeded at that. But the report’s defensive tone about reverting suggests the council recognises the trade-offs have been more severe than anticipated.

What the report doesn’t measure

Perhaps most revealing is what the report chooses not to quantify.

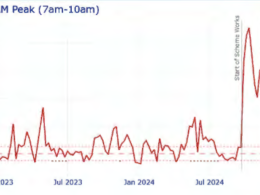

There are detailed measurements of pedestrian crossing times, cyclist volumes, and signal phase durations. There are collision statistics and bus journey time data. But there is no systematic attempt to measure or document the extent of queuing that residents experience daily.

The report notes in passing that queues on Lower Richmond Road and Putney Bridge Road “have significantly increased.” But how long are these queues? How long do vehicles wait? How has this affected journey times not just through the junction, but along the entire approach routes?

At October’s public meeting, residents described the queues as “mile-long.” The report’s focus stays tightly on the junction itself: a strategic choice that keeps the eye on where the scheme has succeeded (pedestrian safety, cyclist protection) rather than where it has failed (traffic flow, residential street impacts).

The side streets problem

The report’s treatment of residential street rat-running exemplifies this selective measurement.

Traffic surveys on five roads off Putney High Street found volumes “below the council’s traffic management intervention level of 300 vehicles at peak hour.” This is presented as evidence that concerns about side streets are unwarranted.

But residents aren’t primarily worried about volume, they’re worried about behaviour. As Harry from Erpingham Road told Hogg last month: “Every morning frustrated drivers are racing up that road as fast as they can to get around the traffic and that’s a school road. There’s people taking their kids to primary school, there are people walking their dogs across the road….

“At some point somebody is going to be killed.”

The 300-vehicle threshold is a traffic management metric designed for different purposes. It’s not a safety standard for residential streets with frustrated drivers cutting through at speed. The report acknowledges surveys were conducted in October on roads off Lower Richmond Road and Putney Bridge Road, but that data is “being analysed” and not included, despite the report being published weeks later.

The timing is unfortunate. These are the streets most affected by the junction queues, and their exclusion from the analysis leaves a significant gap in understanding the scheme’s full impact.

The consultation disparity

The report’s handling of public consultation reveals an organisation struggling to reconcile professional opinion with community experience.

The Putney Action Group’s 1,373 responses were “highly critical.” The council’s response was to commission AECOM to conduct their own survey, which gathered 78 in-person interviews with “positive experiences overall.”

The report [pdf] then goes to some lengths to explain why the 912 additional online responses that flooded in when the survey link was “widely circulated online” should be viewed differently than the in-person responses. These online respondents “expressed markedly more negative views,” the report notes, and “may have been affected by external factors such local campaign groups’ commentary accompanying social media posts.”

This is not unreasonable methodology: in-person responses at the site do provide different insight than online surveys completed away from the junction. But the framing reveals the council’s discomfort with the scale of negative feedback. When 1,373 residents respond to a community-organised survey with near-universal criticism, and 912 people seek out the council’s own survey to register complaints, this isn’t a social media phenomenon, it’s a constituency demanding to be heard.

The report positions positive feedback from two organisations – Wandsworth Cycling Campaign and Wandsworth Living Streets – prominently. Both are legitimate stakeholders. But the report doesn’t mention how many members these organisations represent or how many of their members actually use this junction regularly.

The TfL factor

Transport for London is mentioned 65 times in the report, and never once positively.

TfL rejected safer junction designs. TfL implemented the wrong signal timings (allegedly). TfL requires approval for every change. TfL’s processes take too long. TfL’s bus operations contribute to congestion. TfL’s design standards prevent reverting to the old layout.

There is undoubtedly truth in this. TfL is a notoriously bureaucratic organisation that wields enormous power over London’s roads while maintaining limited accountability to local communities. Its absence from October’s public meeting while representatives attended a meeting about bus changes a mile away in Barnes was telling.

But the relentless focus on TfL’s role serves another purpose: it shifts responsibility away from Wandsworth Council, which designed this junction, paid for it, and championed it through multiple committee votes with unanimous support.

The report was signed by Nick O’Donnell, Director of Growth and Place, rather than a more junior officer. It’s a signal that the council leadership recognises the political significance of this issue. With local elections in May, and residents explicitly threatening to vote Labour out over the junction, this is no longer just a highways matter.

The Hammersmith Bridge assumption

The report explicitly acknowledges that modelling was based on “the standard London wide assumption” that Hammersmith Bridge would reopen by 2026.

This is presented as exculpatory: the junction would work fine if only Hammersmith Bridge were open. But buried in Appendix 2 is a more complex finding: traffic crossing Putney Bridge is actually lower now than in 2018 when Hammersmith Bridge was open.

This suggests traffic displacement from the Hammersmith closure may be less significant than assumed. It also suggests that some traffic has simply “evaporated”; people have changed their behaviour, switched modes, or abandoned journeys entirely.

This is, in transport planning terms, a success. Reduced vehicular traffic is a policy goal. But it makes the junction’s congestion problem harder to explain away. If fewer cars are using the bridge than before Hammersmith closed, why has congestion on the approach roads become so much worse?

The answer returns to the fundamental design choice: the junction was optimised for north-south traffic flow at the expense of east-west approaches. With Hammersmith Bridge open, those east-west approaches might have carried less traffic. With it closed indefinitely, they bear more load than the design can handle.

The learning question

The report concludes with plans for further signal optimisation and additional layout changes, all subject to TfL approval and further modelling.

What it doesn’t include is any reflection on how the original design process produced such unexpected outcomes. There was extensive modelling. Multiple stakeholder consultations. Unanimous committee approval. TfL sign-off. And yet the result has been sufficiently problematic to require £169,000 in emergency fixes within the first year.

At October’s meeting, Hogg acknowledged: “We haven’t said it works. I don’t think you’ve heard from me that I think that it works… everything is on the table to change this.”

This is welcome honesty. But “everything is on the table” is not quite accurate. The council has made clear it will not consider reverting to the old layout. The question now is whether the fixes being implemented can make the current design tolerable, or whether a more fundamental rethink will eventually be unavoidable.

The report shows a council trying hard to save the junction – and perhaps also trying to save face ahead of an election. Whether Thursday’s Transport Committee meeting provides the accountability residents are demanding, or simply rubber-stamps another round of optimistic adjustments, will indicate how seriously the council takes the depth of community concern.

What’s clear from the report is this: a junction designed primarily to benefit pedestrians and cyclists has created severe problems for the majority of people who use it – motorists, bus passengers, and residents of surrounding streets. That’s not a modelling failure or a signal timing error. It’s a policy choice that the council now needs to defend or reconsider.

Great bit of journalism. I cycle acros the bridge running left onto Lower Richmond road most days, and returning.

The new layout doesn’t work for anyone, drivers, cyclists, bus users, even pedestrians, still a huge amount of red light crossings. The people involved are either incompetent or deliberately want to foul Putney’s traffic. The fact that the lights timing was wrongly inputted then, seeing the chaos, nothing was done, is jaw dropping.

Thank you for your excellent reporting and analysis on this debacle.

Great report – I take issue with the councils view that it has improved the life of cyclists, as a regular cyclist along the Lower Richmond Rd it has not. Weaving in and out, being exposed to oncoming traffic, dealing with frustrated drivers who suddenly turn across you to rabbit run, at the exit onto Putney Bridge having no space, plus the obvious increased fumes does not in my view mean improvement ..

I am amazed that they genuinely didn’t expect the outcome that they got. Roads at junctions narrowed for traffic resulted in jams? Who would ever have thought that would happen?

The junction re design has created a traffic flow bottle neck, hence the subsequent increased congestion. Obviously to all that live in central Putney. It needs to be reversed.