More than 880 residents signed petitions. Six planning applications were refused. A private developer went into receivership. And the open space at the heart of the Lennox Estate in Roehampton survived.

As Wandsworth Council seeks planning permission for a 14-storey tower and 81 new homes on the same site, documents from the estate’s archives reveal the remarkable five-year battle that residents fought between 1989 and 1994 to protect their only green space from development.

The story offers a striking precedent for today’s residents, who face proposals for council housing on the northern part of the estate. The council submitted its application in December, triggering a consultation that runs through the Christmas period. But the 1990s campaign shows just how fiercely this community has fought to protect The Green before.

The developer’s gambit

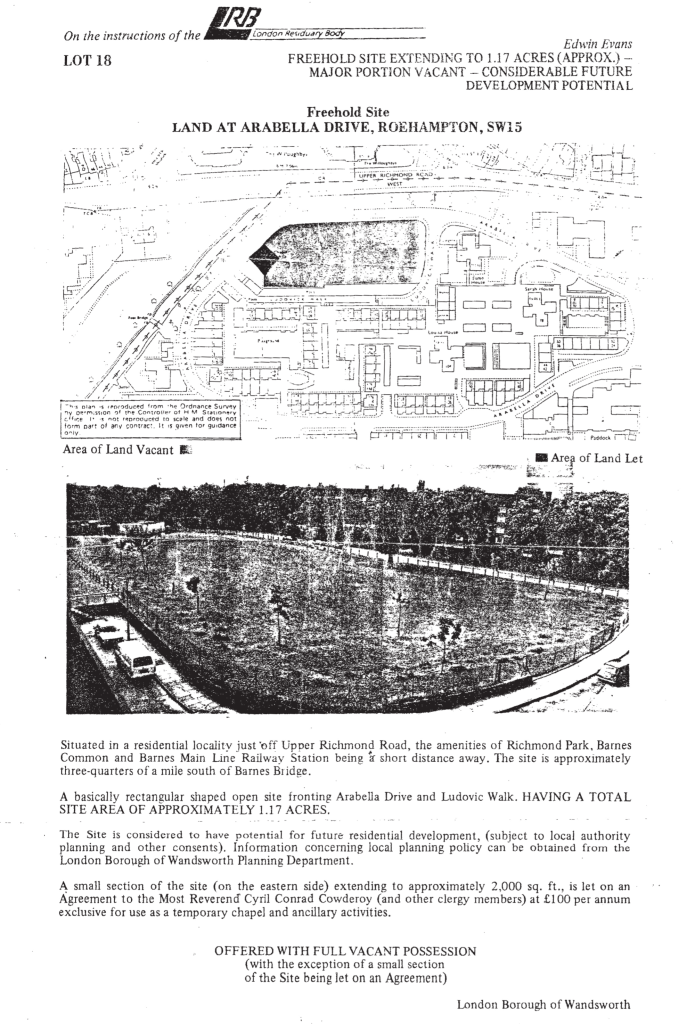

In July 1988, the London Residuary Body auctioned off The Green for £419,000. The buyer was Silven Properties Ltd, a private developer who saw potential in the 1.17-acre site fronting Upper Richmond Road.

The land had been earmarked for a school when the estate was built in the 1960s, but was never developed. In 1973, the Greater London Council agreed it should be “landscaped as temporary open space.” Over the following 15 years, residents made it their own: hosting firework displays, fun days and summer fairs, and using it daily for dog walking, children’s play and simply sitting out.

When Wandsworth Council learned the site was to be sold, officers fought to stop it. In January 1988, the council’s Borough Valuer asked the London Residuary Body to transfer The Green to the council “without charge.” The request was refused. The site was sold anyway.

Silven Properties moved quickly. In September 1989, they submitted plans for 55 sheltered housing flats across two three-storey blocks.

The response was overwhelming. The council notified 342 nearby households. Back came 30 objection letters, 107 additional letters from the Tenants Association signed by 161 residents, and a petition bearing 657 signatures.

“The green is an essential part of everyday existence and an important feature of the estate,” residents wrote. “It is the only place on the estate that is a safe communal recreation and play area for the young and old alike.”

Parents warned that children would be “forced to play in the squares thereby adding to the already intolerable noise level.” Others described the green as “a welcome visual relief from the unrelenting sea of bricks and concrete.”

The council’s planning officers agreed. But before the committee could formally refuse, Silven appealed against “non-determination.” The first appeal was subsequently withdrawn.

A second attempt and a public inquiry

Undeterred, Silven submitted revised plans in September 1990. This time they offered a compromise: one L-shaped block of 55 flats, with 40% of the site (0.47 acres) dedicated as public open space.

The community organised again. This time, 871 neighbours were consulted. At least 150 objection letters arrived, along with a fresh petition bearing 226 signatures.

“We need the Green to remain an open space,” residents wrote. “It is the heart of this estate, the only safe recreational area.”

One submission noted that the green “influenced people’s decisions to buy their properties.” Another warned that approving the scheme would set “a precedent to build on any piece of green land.”

The council refused permission again. Silven appealed, and a public inquiry was held on 29 October 1991 at Wandsworth Town Hall.

Residents sought help from their MP, David Mellor, who then served as a senior minister in John Major’s government. His correspondence with constituents was submitted as formal evidence at the inquiry.

On 13 February 1992, Planning Inspector A.R. Boyland delivered his verdict: appeal dismissed.

The inspector found that the Lennox Estate was objectively deficient in accessible open space. Barnes Common lay across the busy South Circular Road. Vine Road Recreation Ground required crossing both a main road and a railway level crossing. There was simply nowhere else for residents to go.

“It seems to me that the requirement for a small local park within ½ mile walking distance of home is not met for the Lennox Estate,” the inspector wrote.

He rejected the argument that retaining 40% of The Green made the development acceptable: “I have come to the conclusion that it would cause unacceptable harm to the amenities of the residents of the estate in terms of loss of open space, perceived density and loss of outlook.”

Most significantly, he established a principle that would prove crucial: housing need, however pressing, cannot automatically override open space protection where there is demonstrable local deficiency and community reliance.

Four more attempts, then collapse

Silven did not give up. Between 1992 and 1993, they submitted four more schemes, varying between 22 and 40 units. All four were refused.

“Once again the beloved Green is under attack,” wrote one resident in January 1994. “The developers press on, doubtless in the hope that the community’s resolve will finally weaken.”

It did not weaken. But Silven’s finances did.

Before their appeals could reach a full public inquiry, the company defaulted on loans. The Royal Bank of Scotland appointed receivers, who took control of the developer’s assets, including The Green. The Court of Appeal case that followed revealed that receivers sold the site “as is,” as open land, rather than pursuing planning gains that had proved impossible to secure.

By the mid-1990s, Silven Properties’ campaign to build on The Green had definitively collapsed. The company that had paid nearly half a million pounds for the site, hired legal teams and planning consultants, and submitted six separate applications over five years, had been defeated by organised community resistance and sound planning policy.

The legacy, and a new battle

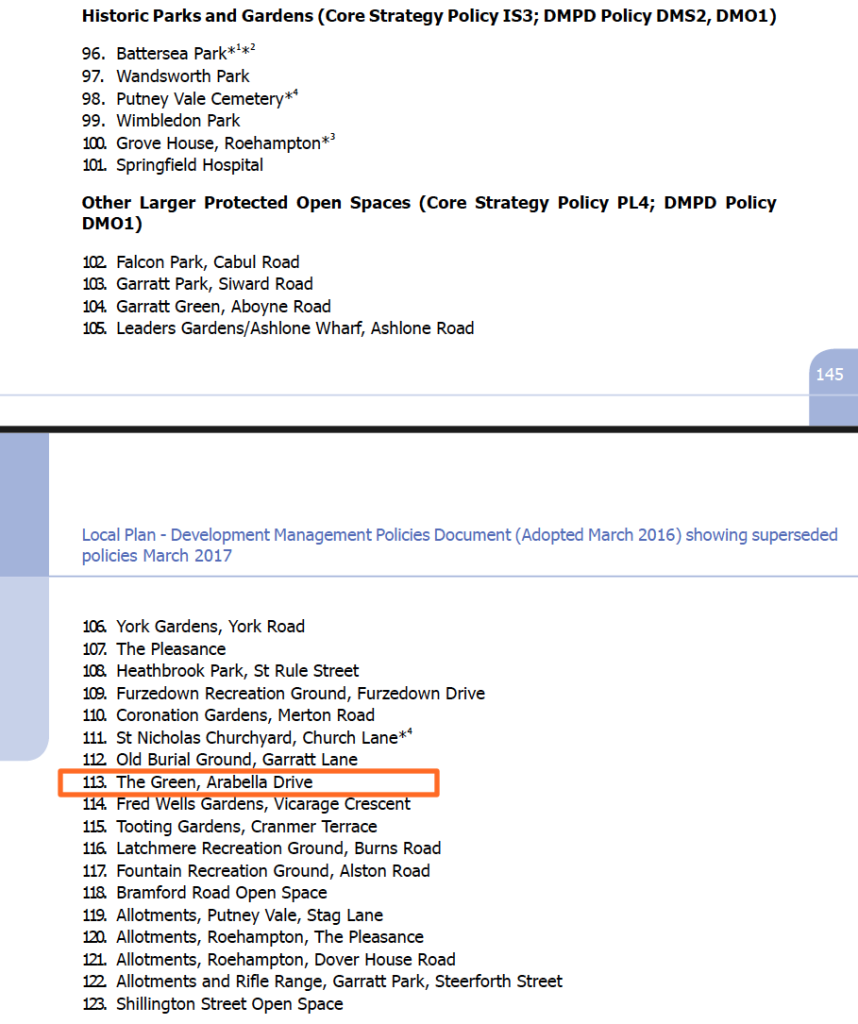

The Green is now formally protected. Wandsworth’s 2016 Development Management Policies Document lists “The Green, Arabella Drive” among the borough’s “Other Larger Protected Open Spaces.”

The 1992 inspector’s decision established a principle that remains relevant today: open space serving a demonstrable community function, in an area of documented deficiency, cannot simply be traded away for housing numbers.

Whether that principle will hold in 2026 is now being tested. Wandsworth Council has submitted a planning application (2025/4170) for 81 council homes and a 14-storey tower on the same Arabella Drive site. The public consultation closes on 19 January.

There is an uncomfortable irony at the heart of the current battle. In 1988, it was Wandsworth Council that fought to protect The Green, with officers urging the London Residuary Body to transfer the land “without charge” rather than sell it to developers. Now the council is itself the developer, and residents face the same question their predecessors answered 35 years ago.

The council says the scheme will provide “new and improved green open spaces.” Residents can judge for themselves whether that promise is enough, and whether they will once again fight for the green space at the heart of their estate.

Comments can be submitted through the council’s planning portal under reference 2025/4170.